Several years ago, my husband lost his dream job. I took on the role of primary breadwinner as he searched for a new position. The search didn’t go as we hoped, and he never returned to full-time employment.

Even though we loved each other and wanted the best for each other, our marriage went through some difficult stretches during that time. It took a few years, but God healed and restored us. Today, we are happy and content even though I still hold the role of breadwinner.

Even Christian wives can struggle with unwanted changes that negatively impact their marriages. To support these women, I published a book, Love Beyond Labels – When Finances Flip.

If you are curious about female breadwinning trends, read on!

If you don’t like numbers and statistics, you may want to skip my next couple blogs. Then join back in when I start covering topics from the book. Those will be full of stories and Biblical principles, just like the book.

Research on breadwinning

The 1982 to 2022 Annual Social and Economic Supplements [1] summarized trends based on U.S. Census and related data. The number of wives who earned more than their husbands grew from 16% to 30% over the last thirty years.

Most reports, however, including a recent Pew Research Study [2], would only refer to these women as breadwinners if they earned 60% or more of family income.

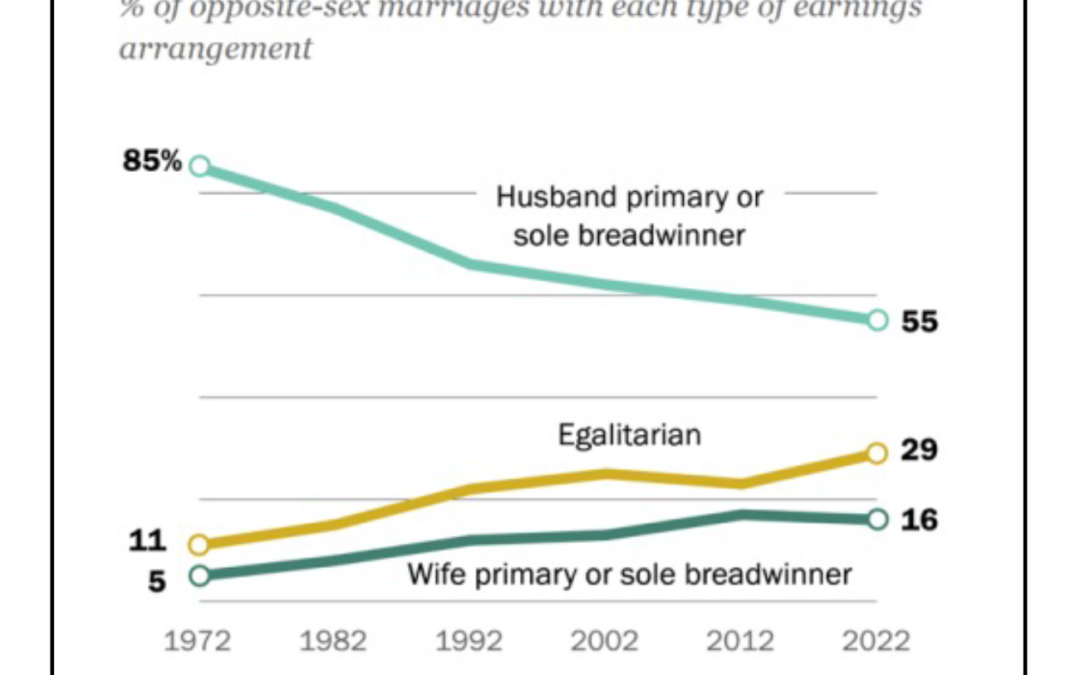

The graph displays the results of the Pew study of traditional marriages.[2]

The most noticeable trend is that there are fewer male breadwinners every year.

Women have been earning more bachelor’s degrees than men for decades and also been welcomed to a wider variety of job opportunities, so this is not a surprising result.[3]

The Egalitarian line shows marriages where both spouses earn similar incomes (40%-60% each).

The report also breaks out percentages based on factors like age, number of children, race, and income level. The highest percentage of female breadwinners fell along one particular racial line, but even in that category, only 26% of women were breadwinners while 40% of the men were breadwinners. Therefore, we can safely say that it is still much more common for men to be the primary wage earners.

Looking more closely at the chart above, I saw something interesting. The female breadwinner graph line leveled off around 2012 and has stayed around 16%.

You may be asking the same question I asked when I first saw this chart: If women have more earning opportunities today than in 2012, then why hasn’t the number of breadwinner wives continued to climb?

It also happens in Europe. One study looked at income earning in 27 countries. All countries shared a common feature the report referred to as the “cliff.”

Let me try to explain the cliff. Many wives contribute just a little bit less than or just as much as their husbands. Then there is a steep drop off after the 50/50 point. In other words, percentages rise until the husband and wife make similar incomes. After that point, there is a significant drop in the number of women who earn more than 60% of the household income.[4]

Why is that?

Read the next blog to learn about hypotheses about the “female breadwinner penalty.”

[1] Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, 1982 to 2022 Annual Social and Economic Supplements (CPS ASEC).

[2] Parker, R. F., Carolina Aragão, Kiley Hurst and Kim. (2023, April 13). In a growing share of u. S. Marriages, husbands and wives earn about the same. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2023/04/13/in-a-growing-share-of-u-s-marriages-husbands-and-wives-earn-about-the-same/

[3] Hurst, K. (2024, November 18). U.S. women are outpacing men in college completion, including in every major racial and ethnic group. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2024/11/18/us-women-are-outpacing-men-in-college-completion-including-in-every-major-racial-and-ethnic-group/

[4] Grow, A., & Van Bavel, J. (2020). The gender cliff in the relative contribution to the household income: Insights from modelling marriage markets in 27 European countries. European Journal of Population, 36(4), 711–733. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-019-09547-

Recent Comments